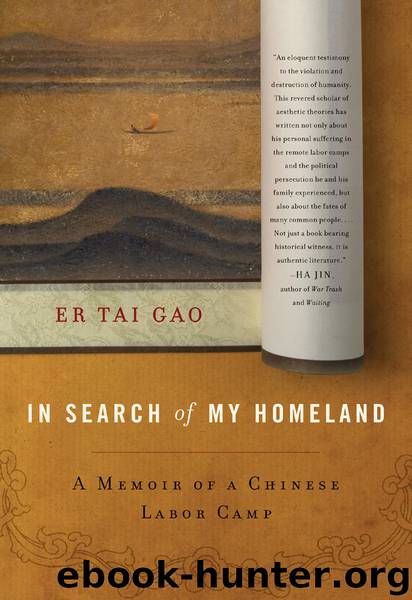

In Search of My Homeland by Er Tai Gao

Author:Er Tai Gao

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins

Published: 2009-09-22T04:00:00+00:00

TWENTY-TWO

Initiation

When the National Research Institute for Dunhuang Art was established in 1944, the first director was the famous painter Chang Shuhong. In 1950, the second year of the new political regime, the Institute was taken over by the Cultural Relics Department of the Cultural Bureau of the Northwest Military Committee of the People’s Republic, and its name changed to the Dunhuang Cultural Relics Research Institute. The existing personnel were kept on, and Chang Shuhong was reappointed as director.

When I got there in 1962, there were forty-odd people in the Institute, divided among the Research Department, the Administrative Department, and the Cave Preservation Department. The director, Chang Shuhong, was concurrently president of Lanzhou Arts College, and he did not spend much time at Dunhuang. The day-to-day business at Dunhuang was almost all undertaken by his wife, Li Chengxian, who was Party branch secretary and deputy director. At the same time Li Chengxian was head of the Research Department and was in charge of the professional work as well as personnel matters, services, and political thought work.

Li was a painter by vocation, and having spent some twenty years tracing wall paintings at Dunhuang, was highly competent professionally. She joined the ranks of the leadership after becoming a Party member; she displayed exceptional enthusiasm for politics, making heavy demands on one and all. Impetuous by nature, she was blunt and sharp-tongued. When something came up, she could not contain herself; she had to enquire right away, investigate right away, and did not disguise her feelings. As her subordinate, you could read her face as a barometer of the political climate, which relieved you of trying to read riddles, and so was very welcome.

Nominally the Research Institute was directly answerable to the Ministry of Culture of the central government, but in practice the Party organization, which ran everything in the Institute, was a branch of the Propaganda Department of the Dunhuang County Committee, so in effect we came under the direction of that committee. Whenever the county took some action, the Institute was informed. The Institute had a medium-size bus, and our whole staff—Party members and non-Party members alike—often rode it to the county seat fifteen miles away to hear all kinds of reports: communicating the gist of a certain meeting, implementing some policy, mobilizing to emulate Daqing, or Dazhai, or the People’s Liberation Army, or some hero or model or other, and so on.1 When we got back, we discussed and followed through, cutting no corners.

For the ten or more years prior to my arrival, that had been the case. So although the Research Institute was an isolated island in the far reaches of a sea of sand, a place for the study of remote forms of ancient art, it was by no means cut off from the world. Successive political movements, like those used to suppress counter-revolutionaries, to eliminate counter-revolutionaries, and the Three-Anti, Five-Anti, Anti-Rightist, and Anti-Right-Deviationist struggles, had all gone on with great gusto. Sometimes the Institute was a bit slow getting off the mark, but it never simply went through the motions.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Becoming by Michelle Obama(10033)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5768)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5643)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4612)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3996)

The Five People You Meet in Heaven by Mitch Albom(3575)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3548)

The Choice by Edith Eva Eger(3479)

Full Circle by Michael Palin(3455)

The Mamba Mentality by Kobe Bryant(3289)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3039)

Imagine Me by Tahereh Mafi(2972)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2943)

The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande(2863)

Less by Andrew Sean Greer(2701)

A Burst of Light by Audre Lorde(2614)

The Big Twitch by Sean Dooley(2440)

No Room for Small Dreams by Shimon Peres(2376)

Everest the Cruel Way by Joe Tasker(2347)